China's Red Musics

Music and the Development of National Identity under Communist Rule

In twentieth-century China, performance was never just about entertainment. It was a crucial medium through which the Chinese Communist Party (CCP) constructed and communicated its vision of a new socialist nation. From the founding of the People’s Republic in 1949 to the end of the Cultural Revolution in 1976, the CCP used theater, music, and opera to reshape national identity and reinforce political ideology. Among the most prominent examples of this effort were the yangbanxi, or model works, which emerged as highly controlled revolutionary performances that replaced traditional operas and literature. These productions elevated idealized images of workers, peasants, and soldiers while condemning remnants of China’s feudal and capitalist past.

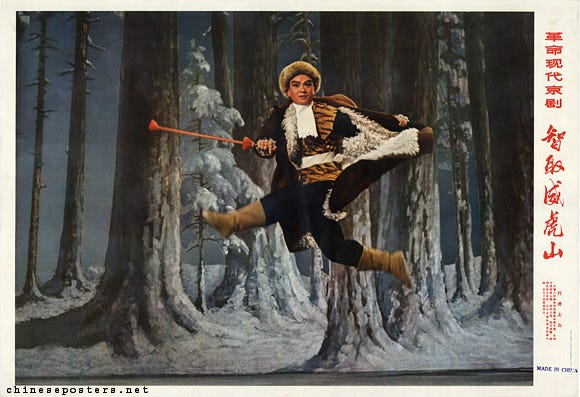

This blog examines how model works developed as ideological tools, beginning with the Party’s early efforts to rebuild the cultural landscape following the Chinese Civil War. Traditional forms like xiqu were adapted to suit revolutionary narratives, with scripts rewritten and roles recast to reflect Maoist ideals. We will explore operas like The Legend of the White Snake and The Taking Tiger Mountain by Strategy (1970), which were transformed under close state supervision, turning familiar stories into powerful expressions of class struggle and collective heroism. These works were not isolated performances; they were integrated into everyday life through newspapers, schools, film, and even loudspeaker broadcasts, embedding the Party’s messages into the rhythms of daily experience.

Following the end of the Cultural Revolution, the role of these works changed. Once symbols of political propaganda, model operas faded from public favor but eventually returned in new forms. In the Reform Era and into the present day, they have been revived through nostalgic performances, pop culture adaptations, and reinterpretations like Tsui Hark’s 2014 remake of The Taking of Tiger Mountain. These contemporary versions shift the focus away from rigid ideology and instead emphasize individual heroism, artistic merit, and shared cultural memory. In tracing the trajectory of model works from instruments of propaganda to evolving cultural artifacts, this blog explores how revolutionary art can both reflect and shape national identity. It also raises questions about how collective memory is preserved, altered, and repurposed across generations in response to changing political and cultural contexts.

Historical Background: 1949-1964

On September 21, 1949, Chairman Mao Zedong proclaimed, “The Chinese people have stood up!” 中国人民站起来了!and announced the founding of the People’s Republic of China after emerging victorious from the Chinese Civil War. The sociopolitical situation in China after the end of the Chinese Civil War in 1949 had left a divided society, failing economy, with the population having no faith in their leadership. In order to prove legitimacy, increase morale, and gain support, the Chinese Communist Party (CCP) sought to reconstruct China’s cultural landscape, as Mao and Party leaders realized that to gain support of the people, they had to initiate a nationwide cultural renewal. Cultural elements such as music and opera became the focus of Mao’s reform; after the CCP emerged triumphant, the May Day and National Day parades embraced a new era of socialism, and displayed the achievements under communism through bright floats, red banners, balloons, revolutionary (red) songs and performance theater, which would later evolve into the model works (Hung 2011, 11).

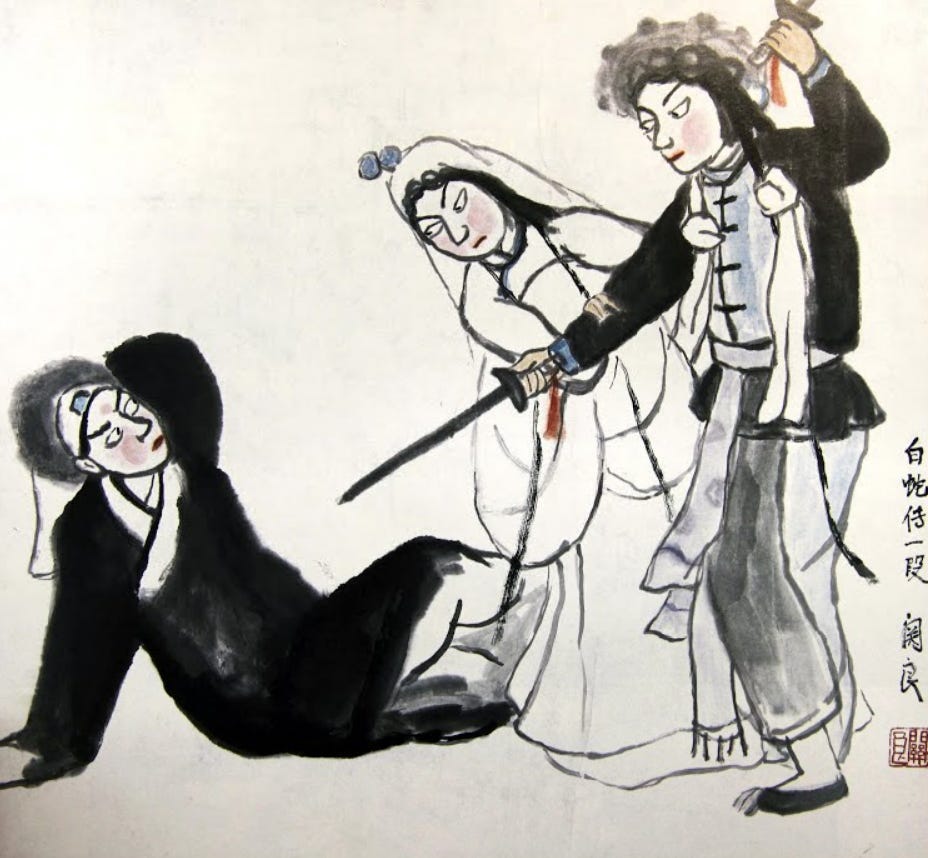

Evidence of this cultural shift is found in historical records of popular drama, political theater, peasant operas, language and propaganda of Chinese politics, official art policies, Chinese cinema, and the Party’s control over artists, intellectuals, and writers (Hung 2011). An example of this can be seen in the publication process of The Legend of the White Snake 白蛇传, which was written three times before publication in 1950. The Legend of the White Snake belongs to the genre of xiqu 戏曲, which is the family of theatrical genres commonly referred to in the West as “Chinese opera.” Like many other xiqu works during this time, important figures in the CCP’s propaganda machine like the Ministry of Culture’s head of propaganda Zhou Yang, Peking opera director Li Zigui, and respected senior Peking opera performer Wang Yaoqing embraced The Legend of the White Snake, and molded it into a tool for reconstructing China’s cultural landscape (Rebull 2017, 33).

The Legend of the White Snake was a well-known example of a team of artists and cultural workers shaping a traditional opera script to fit a set of ideological values. After the reform of a given xiqu script, officials encouraged open discussions of these new works in print—articles, reports, and personal testimonies of actors and directors allowed the greater population to gain an understanding of ideological messages and narratives constructed by the Party. (Many of these reporters and journals were members of the CCP’s xiqu reform committee and served as a mouthpiece for the CCP.) Although the Cultural Revolution in China was not formally launched until 1966, the practices of shaping cultural works were embedded during the 1950s, as seen in the Party’s initial effort of “cultural renewal,” and during the early 1960s, through the socioeconomic efforts of the CCP in the Great Leap Forward.

The Great Leap Forward was launched in 1958, a campaign meant to motivate the Chinese people to “go all out, aim high, and achieve greater, faster, better and more economical results in building socialism” and surpass Britain (one of China’s former imperial colonizers) in industrial production within fifteen years or less (Ouyang 2022, 30). From 1958 to 1961, large-scale communal farms were established, and the majority of the population was forced into laboring for industrial projects. The few who did manage agricultural operations sought to please their superiors by overreporting the volume of grain produced and combined with China’s massive population relying on rations of grain, this resulted in widespread famine and an estimated 38 million deaths. As the inconsistencies in these reports grew larger and larger, and civilians were forced to collectivize their and resources, this led the rural populations with no resources to fall back onto during the intense famine.

In the period following the disastrous Great Leap Forward, Chairman Mao briefly lost power, and sought to restore his influence by purging his rivals. In the process of widespread industrialization, Mao found it crucial that the CCP attack the “revisionists” who supported the return of capitalism, and accused his rivals of supporting revisionism. Mao utilized the arts, literature, and educational institutions to transform public ideologies regarding political issues, successfully influencing popular culture for his political agendas (Ouyang 2022, 25).

An example that we discuss further in this blog is the xiqu, Taking Tiger Mountain by Strategy 智取威虎山. In the reformation of this opera, the protagonist Yang Zirong is portrayed as a loyal People’s Liberation Army (PLA) soldier, acting as a symbol of heroism and model citizen of the working class. As we will analyze, Yang serves as a propagandistic symbol of the state’s official ideology, promoting class consciousness, and collective loyalty and faith in Mao and the Chinese Communist Party.

Model Works as an Ideological Tool

During the Cultural Revolution, the CCP pushed for a complete “reset” of Chinese culture. Under Mao Zedong’s leadership and with significant influence from his fourth wife, Jiang Qing, older cultural forms, including even recent state-approved works, were banned in favor of works that supported revolutionary ideals. Traditional opera, literature, and performance were labeled as “feudal” or counterrevolutionary, terms the CCP used to denounce cultural practices associated with China’s imperial past, hierarchical social structures, and Confucian values that conflicted with socialist ideology. In their place came a new set of highly controlled productions known as yangbanxi 样板戏, or model works (Mittler 2012, 12; Chen 2002, 45–48).

The model works initially numbered eight at the start of the Cultural Revolution, but by its official end, the repertoire had expanded to eighteen, including ten operas, four ballets, two symphonies, and two piano pieces (Mittler 2012, 36). These model works were not simply forms of entertainment, as each one focused on specific historical episodes such as the Sino-Japanese War or the Korean War, and emphasized themes like class struggle, revolutionary heroism, and loyalty to Mao and the Communist Party (Mittler 2012, 16).

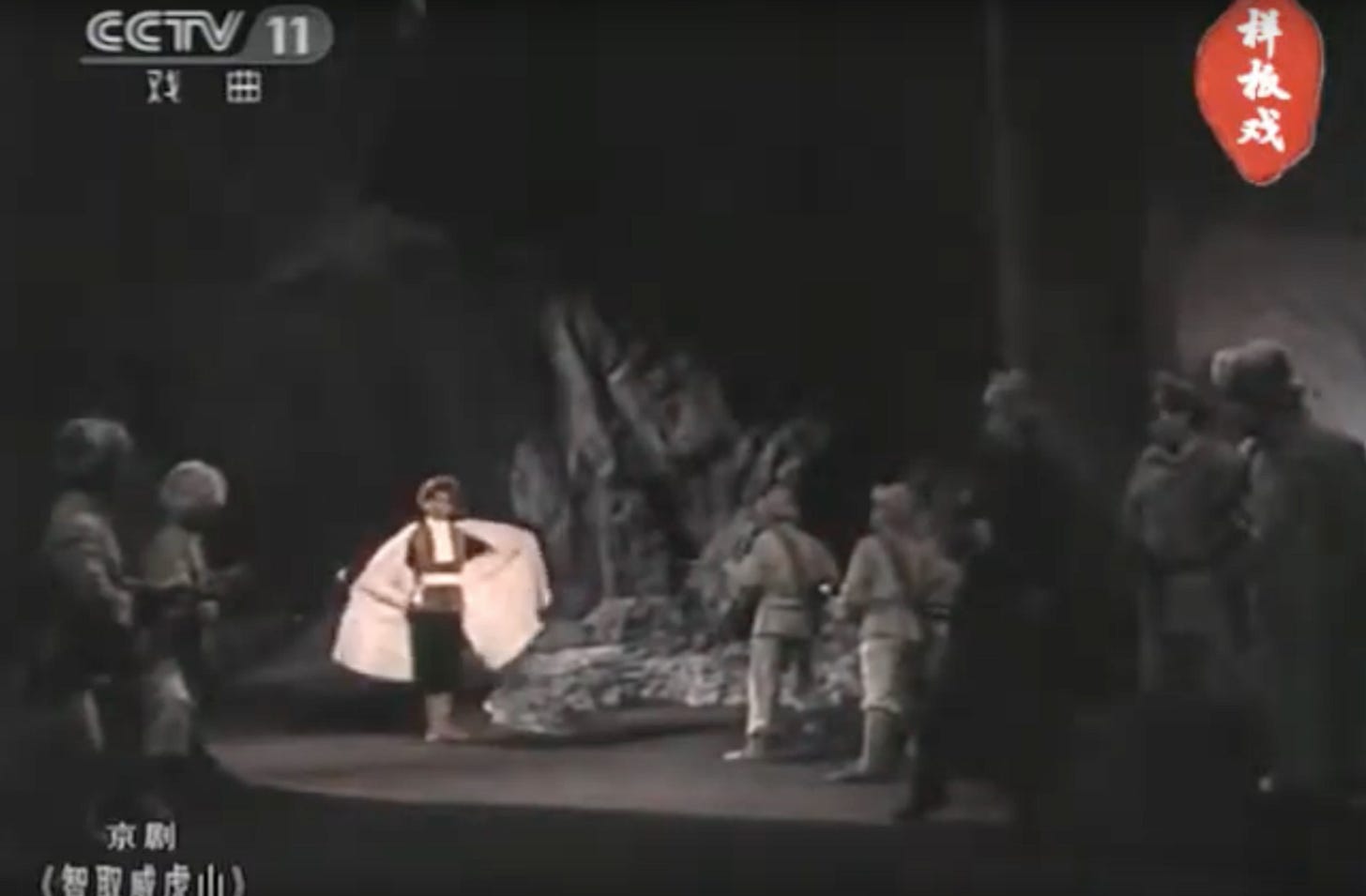

At the center of these productions was the CCP’s belief that traditional art forms embodied values incompatible with socialist ideals. Under Mao’s leadership, art was transformed into a tool for political and ideological education, with model works designed to promote loyalty to the Party and reinforce a collective revolutionary identity. These productions commonly glorified workers, peasants, and soldiers, while portraying capitalists, imperialists, and landlords as enemies of the people (Mittler 2012, 36). The operas simplified these social conflicts into a clear binary, reinforcing a moral universe where revolutionary subjects stood in opposition to enemies of the state. This ideological clarity was not only textual but also visual. Take for example figure 3, a scene from the 1970 film adaptation of The Taking of Tiger Mountain by Strategy, where the protagonist Yang Zirong is isolated in bright lighting at the center of the stage, visually emphasizing his heroism and moral authority. In contrast, the surrounding bandits are cast in darkness, their shadowy presence reinforcing their role as anti-PLA villains and ideological enemies. Such staging choices served to visually encode the CCP’s political binaries, reinforcing Mao as the ultimate source of wisdom and depicting revolutionary success as dependent on unwavering obedience to Maoist thought (Chen 2002, 81–83).

Mao’s wife Jiang Qing played a decisive role in shaping this artistic vision. Formerly an actress in Shanghai’s leftist film scene, she oversaw the creation of model works with strict ideological control. She enforced strict ideological oversight and promoted the “Three Prominences”: the idea that the hero must stand out most, that positive traits must outweigh negative ones, and that the central character must remain the narrative focus. These principles ensured that protagonists, especially PLA soldiers, not only carried the story but also served as role models for revolutionary behavior (Chen 2002, 106-108). By emphasizing clear distinctions between good and bad, the Three Prominences helped make art a powerful tool for spreading Maoist ideology and presenting the revolution as historically necessary and morally righteous.

Propaganda and Performance

The Taking of Tiger Mountain is widely considered one of the most iconic model works, frequently analyzed as a representative example of revolutionary opera (Mittler 2012, 68). Based on Qu Bo’s novel Tracks in the Snowy Forest 林海雪原, the opera tells the story of a PLA soldier infiltrating a bandit stronghold in northeast China. The protagonist, Yang Zirong, goes undercover and ultimately leads the army to victory. His discipline, courage, and loyalty to the Party present him as the ideal Communist hero.

The opera blends elements of traditional Chinese singing with Western symphonic instrumentation, producing a hybrid musical style that was both recognizable and novel to audiences of the time. While some features such as the operatic vocal delivery resembled earlier forms like Peking opera, these were carefully restructured to serve revolutionary narratives. As Barbara Mittler explains, model works like The Taking of Tiger Mountain appropriated both Chinese and Western musical forms not to preserve cultural roots, but to transform them into ideological tools aligned with Maoist principles (Mittler 2012, 68–69). Songs like “We Will Take the Tiger Mountain by Strategy” were crafted with catchy melodies and strong emotional appeal, reflecting the CCP’s broader goal of making revolutionary ideology accessible and memorable. Mittler further notes that the musical language of model works “created an atmosphere of ‘Revolutionary Realism and Revolutionary Romanticism,’” designed not simply to entertain but to persuade and unify audiences around Maoist ideals (Mittler 2012, 69).

These model works were not optional. To saturate everyday life with revolutionary messaging and ensure ideological conformity, the CCP relied on a vast network of over six million loudspeakers to broadcast model works daily and staged performances in schools, factories, military bases, and rural villages (Jones 2020, 53–60). Attending a model work became more than just watching a performance, it became a public demonstration of political loyalty. While these works were carefully designed to appear emotionally engaging and persuasive, audience reception was often performative rather than sincere. As Xiaomei Chen argues, many citizens practiced what she calls “performed loyalty”: they applauded when expected and outwardly displayed enthusiasm, but often did so out of obligation, fear, or social pressure rather than genuine appreciation (Chen 2002, 9). Journalist Gino Nebiolo’s account of a 1973 performance reflects this contradiction. Although he described some audience members reacting with attention or emotion, he also noted that much of the audience clapped mechanically and without visible engagement. These responses suggest that many viewed participation in model works not as meaningful cultural experiences, but as acts of political survival (Mittler 2012, 11-16).

Historicizing Model Works and Red Songs

After Mao Zedong’s death in 1976, the Cultural Revolution came to an abrupt end. In a widely publicised trial, Jiang Qing’s so-called Gang of Four, the figureheads of the Cultural Revolution, were charged with treason and sentenced to life imprisonment. The era of Mao was over. Starting in 1978, under the leadership of Deng Xiaoping, the CCP distanced itself from the Cultural Revolution and redirected the country toward modernization and reform. China opened its economy to foreign investment through the special economic zones, which marked a sharp departure from Maoist ideology.

Culturally, this transition sparked a public condemnation of anything associated with the Cultural Revolution and led to growing space for literary, intellectual, and historical critique (Cook 2016). The Gang of Four were criticized for suppressing China’s artistic output and promoting cultural stagnation. A common joke against the Cultural Revolution was “eight (theatrical) works for 800 million people, and that’s all” (Mittler 2012, 46). The Three Prominences approach was criticized for creating excessively formulaic and contrived dramas (Mackerras 1979, 5). The end of the Cultural Revolution also resulted in less government oversight of what media was allowed to be consumed or performed. In his 1977 visit to China, Theater scholar Colin Mackerras noticed that the most popular plays being performed were those that were popular pre-Cultural Revolution but that had been suppressed. He could only find a few performances of select scenes from model works (Mackerras 1979, 9). The model works “faded into obscurity, only to regain popularity in the 1990s amidst a broader commodification of nostalgia for socialist ‘red culture’” (Ferrari 2025).

By the 1990s, China’s reform era was well underway, and a new perspective on the Cultural Revolution, including the model works, began to emerge. The 90s saw a resurgence of popularity in Cultural Revolution media and increased nostalgia for the Mao era. Model works were performed at sold out shows and were sold as DVDs on the open market (Mittler 2012, 50). A major reason for this resurgence was nostalgia for Mao era China, particularly among those that grew up during the Cultural Revolution. Lei Ouyang conducted numerous interviews of people that grew up during the Cultural Revolution and their reactions to music of that era. The overwhelming majority of them associated the music with a deep nostalgia and positive memories of their childhood. They liked the songs more for the memories of singing them together with their community rather than their political messages. Mao era China was associated with a simpler life with less crime and consumerism (Ouyang 2022, 116). Because of their prevalence in everyday life, model works and other Cultural Revolution media were remembered beyond their original context. Instead of their political significance, Cultural Revolution media were valued because they evoked nostalgia and a sense of community.

In addition, the model works became more valued for their artistic and cultural merits. They have been reappraised as significant artistic achievements, often praised for their integration of traditional Peking opera with foreign musical and dramatic elements. As one museum curator noted, “They are a kind of renewal of Beijing [Peking] Opera. The best people were involved in their production … Of course, they are very political, but they are Beijing [Peking] Operas all the same” (Mittler 2012, 90). This perspective suggests that the model works are now viewed as a unique synthesis of traditional and foreign influences, which “are artistically as accomplished as little else was in the history of cultural development throughout twentieth-century China” (Mittler 2012, 91).

Since the end of the Cultural Revolution, government control over model works and other media has lessened. This has resulted in the model works being reimagined. For example, the main aria of Taking Tiger Mountain by Strategy, was performed in an a cappella arrangement on the Chinese singing competition Sound of My Dream. Yang Zirong, the protagonist, has been replaced by a seven person a cappella group. The members of the group are dressed in modern clothing and stand still throughout the entire performance. Yang Zirong’s iconic tiger costume and impressive acrobatics are nowhere to be seen. The lead singer sings with the same tone and virtuosity as the original performer while the instruments have been replaced by people vocalizing. This performance effectively conveys the main melody of the aria, capturing the rhythmic feel of a galloping horse, with one member even mimicking a neigh. What is most interesting is the enthusiastic reaction of the judges and audience. They seem to be familiar with the aria as the camera shows them singing along. In addition, none of the judges’ comments were about if they stayed faithful to the original or the political messages of the model work. They were more impressed with the a capella arrangement and the virtuosity of the lead singer.

While this example shows how model works are now appreciated for their artistic merits, it also indicates a shift in the CCP’s attitude towards Cultural Revolution media. Keep in mind that this performance was on Chinese national television, which is heavily regulated. A national broadcast of a model work would have been unthinkable in the years following Mao’s death. It seems most likely that this performance was allowed since it was a new, hip way to introduce this model work to a modern Chinese audience and promote socialist values.

In Xi Jinping’s China, government control of the media and the promotion of Cultural Revolution values has increased, reflecting a resurgence of nationalism and state-driven narratives. Xi’s 2014 speech at the Conference on Literature and Art echoed Mao’s Yan’an talks, emphasizing the need for art to serve socialist values and the Party’s ideological goals. In 2018, the CCP banned depictions of hip hop culture, subculture, and decadent culture on television. Through his rhetoric, Xi indicated that the CCP should control the media and make sure it promotes social values (Ouyang 2022, 146). Additionally, model works were performed during the CCP’s centenary celebrations in 2021, and new plays were created featuring frontline medical workers as the heroes (Ferrari 2025). Xi’s actions reflect an attempt to evoke a nostalgia for a simpler, more ideologically unified era amidst China’s rapid social transformation and globalism.

Model Works Today: Reaching the Younger Audience by Cannibalizing Memory

Tsui Hark’s 2014 remake of The Taking of Tiger Mountain enters the landscape of Chinese cinema not as a mere homage to a revolutionary classic, but as a bold reimagining of a foundational national myth. Framed by a present-day Chinese student watching the original film in New York, the story follows PLA scout Yang Zirong as he infiltrates a bandit gang led by the warlord Hawk. The story itself remains true to the original opera, however Tsui repositions the narrative as a dynamic, living memory by fusing it with a metafictional structure. He separates the original film by framing it as a work of fiction, while presenting his own rendition as one informed by historical evidence and lived experience. Ultimately, his reinterpretation of the story aided the simultaneity of the Chinese national identity.

Tsui infuses the remake with kinetic camera work, CGI-enhanced landscapes, and intense action sequences (fig. 5). This later rendition contrasts sharply with the original film, which relied on static staging and theatrical performance conventions tied closely to its propagandistic goals. He deliberately avoids political messaging as the main focus of the story, transforming it from collectivist performance to a globally influenced cinematic language. As critic Noel Murray notes in his review of the movie, “Tsui does fulfill his primary goal here of making a classic newly relevant—not just to younger Chinese viewers, but to anyone who likes action. There’s something universal about honor, sacrifice, and gun-toting dudes on skis” (Murray 2015). Tsui’s storytelling style remakes the revolutionary myth as accessible for any type of audience.

Tsui’s reimagining not only makes the revolutionary tale more visually engaging for younger audiences, but also reshapes their relationship to it by “cannibalizing” collective memory through his layered narrative framing. To cannibalize memory, in this context, means to extract elements from a shared historical or cultural past and repurpose them to construct something new. As defined by Collins Dictionary, “cannibalizing” involves taking parts from one thing to create another. Tsui draws upon the collective memory of the Cultural Revolution in the form of the model opera, and reshapes it, not to preserve its original ideological intent, but to reframe it within a contemporary cinematic language. In doing so, he crafts a version of the past that feels familiar yet fundamentally transformed.

Hui Fang, an assistant professor in the School of Journalism and Communication of Jinan University, describes several features of Tsui’s “cannibalization,” which the author divides into three separate stages: minimization, displacement, and transportation.

The first aspect, minimization, describes how the ideological content is diluted in Tsui’s movie (Fang 2020, 779).While the original film highlights the Communist Party’s class struggle and agrarian reform, Tsui’s version shifts the emphasis toward individual heroism rather than overt political messaging. From Murray’s review, Tsui intends to revive the spirit of honor across generations, not political loyalty, “Tsui has said that he was on a mission with this project, intending to prove the value of a story that’s been firmly planted in the Chinese national consciousness for half a century” (Murray 2015). As a result, the film returns to the spirit of its original source—a novel written before its adaptation into Cultural Revolution propaganda—and presents characters with more nuanced, less rigidly class-based characterizations.

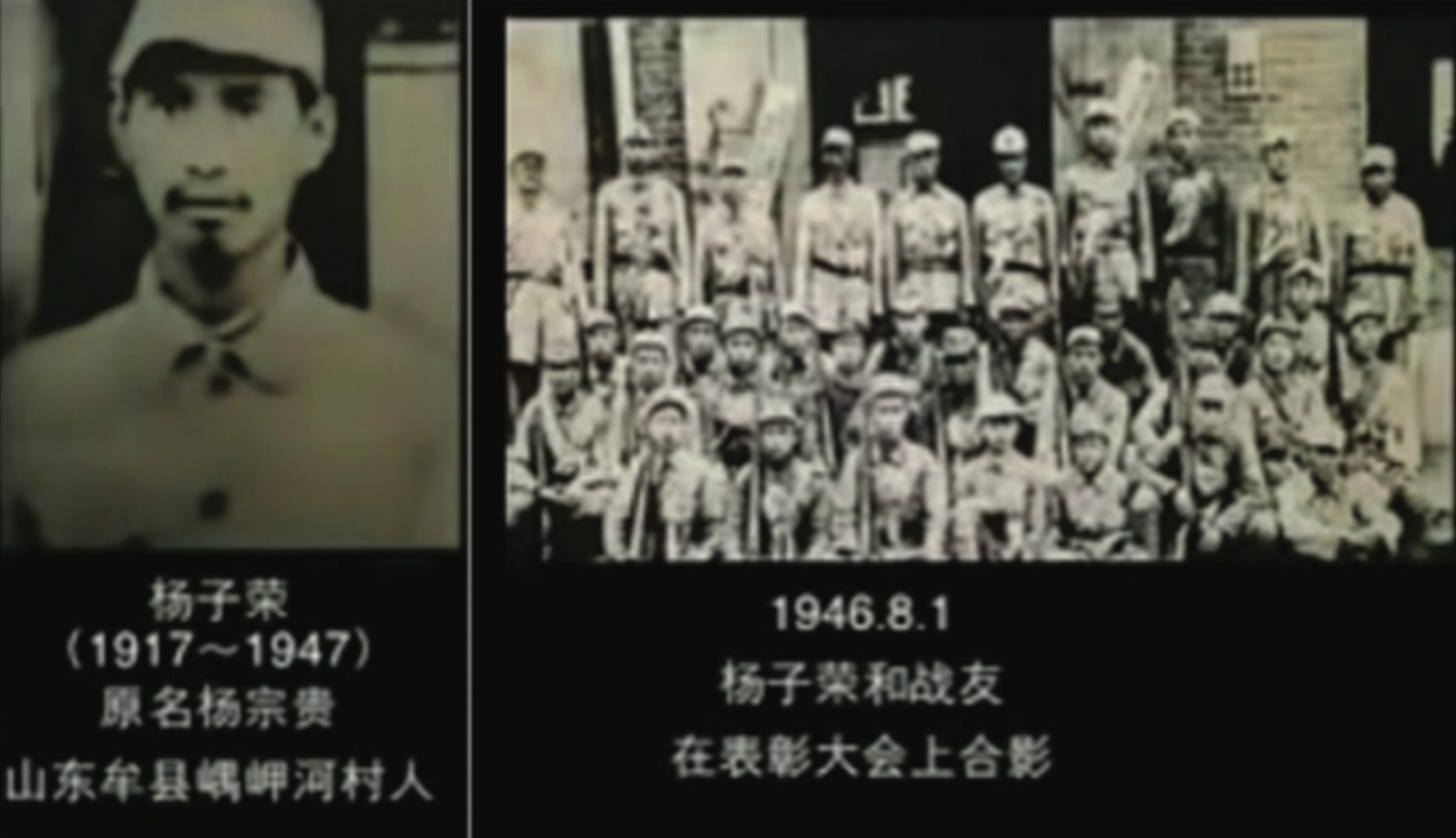

Fang’s second aspect of cannibalization is displacement, where Tsui uses seemingly authentic historical references to frame the story (Fang 2020, 780). This is shown through the inclusion of archival photographs of the real Yang Zirong at the end, offering a realist touch. Tsui successfully distances the character from the heavily idealized version in the model opera, recontextualizing him within historical memory.

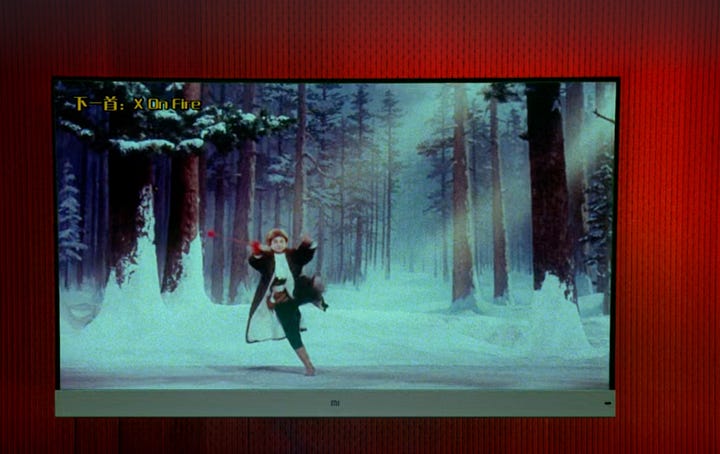

The final aspect of cannibalization is called transportation, where familiar meanings or associations from one context are carried over and used to describe or represent different experiences (Zelizer 2011, 33). Tsui separates the ideological associations from the Cultural Revolution by intentionally portraying it in fictional media (Fang 2020, 780-781). Rather than sustaining connections to Maoist propaganda, the remake recasts the opera’s motifs as part of a nostalgic pop-cultural past—linked more to karaoke and television than to history. This is evident in the beginning and ending of the movie where the movie directly references the original movie. As the movie starts, we follow a Chinese student studying abroad in New York City. The beginning sequence is shown in Figure 7, where the student feels inspired as he coincidentally sees the original movie of the model work version of Taking Tiger Mountain displayed on a karaoke TV screen. Tsui employs the same strategy at the end of the film, where the original movie is again displayed on TV, connoting a fictional world. Tsui ultimately reduces what used to be propaganda to a fun form of entertainment and nostalgia. In doing so, Tsui presents his version as a more “truthful” retelling of Chinese history by anchoring itself to actual historical events, distancing itself from the overt propaganda of the original film. By framing the model work as fiction and his adaptation as a biographical narrative, Tsui transforms the collective memory of the revolution into something more cinematic, personal, and palatable for modern audiences.

Tsui Hark’s The Taking of Tiger Mountain is not merely a visual or narrative upgrade of a revolutionary classic. Rather, it is a cinematic intervention in the evolving construction of Chinese national identity. Tsui successfully reframes a historically orchestrated piece of propaganda to a timeless, heroic narrative preserved through modern aesthetics and storytelling devices.

Tsui’s film offers viewers a shared cinematic moment; a new way for disparate viewers to engage with a national myth, together and in the present tense. The film’s modern framing device, cutting between historical battle and present-day reflection, creates a layered simultaneity: viewers are encouraged to experience the past not as distant and resolved, but as alive and in motion. In this way, Tsui offers viewers a new version of what Benedict Andersion referred to as simultaneity, under his conception of imagined communities. In Anderson’s terms, the nation is imagined as a sociological organism that moves “calendrically through homogenous, empty time,” where citizens believe in the parallel, continuous existence of one another despite never meeting (Anderson 2006, 26). The film’s modern framing device helps sustain the idea of China as a continuous, unified national subject—one that looks backward not with nostalgia, but with active reinterpretation.

Conclusion

Model works from the Cultural Revolution have had a lasting impact on Chinese culture and society. They shaped national identity through carefully crafted narratives of heroism, class struggle, and devotion to Mao. Throughout this blog, we have explored various dimensions of this influence, with particular attention to The Taking of Tiger Mountain (1970). Originally conceived as a tool of propaganda, the opera has since evolved into a story centered more on the heroism of Yang Zirong than on ideological messages alone. However, in the years following the Cultural Revolution, these works have become repurposed through nostalgia, artistic interpretation, and popular culture. Xi Jinping’s efforts to promote socialist values through propaganda and revival of model works are similar to Mao’s Cultural Revolution. In a way, Xi is attempting to cannibalize the collective memory of the Cultural Revolution, evoking nostalgia for an era that was neither peaceful nor egalitarian. The prevalence of Cultural Revolution ideas and media in Xi’s China highlights how art created for propaganda can have an enduring effect on the public consciousness and be reimagined across generations.

Ultimately, the enduring relevance of model works lies in their capacity to shift meaning across time. Drawing on Benedict Anderson’s concept of simultaneity, we can see how the narrative framing of China’s revolutionary past creates a perception in which the past is not simply behind us, but persistently present. Through state-endorsed revivals and reinterpretations, the Cultural Revolution is not just remembered but it is re-lived in ways that collapse historical distance and blur the line between then and now.

Model works remain vital spaces where politics, performance, and national identity converge. Their ongoing transformation raises urgent questions about how collective memory is produced, who holds the power to shape it, and how the past continues to inform and complicate the cultural narratives of the present.

Works Cited

Anderson, Benedict. Imagined Communities: Reflections on the Origin and Spread of Nationalism. Verso, 2006.

Chen, Xiaomei. Acting the Right Part: Political Theater and Popular Drama in Contemporary China. University of Hawaiʻi Press, 2002.

Clark, Paul, Laikwan Pang, and Tsan-Huang Tsai, editors. Listening to China’s Cultural Revolution: Music, Politics, and Cultural Continuities. Palgrave Macmillan, 2016.

Cook, Alexander C. “Conclusion.” The Cultural Revolution on Trial: Mao and the Gang of Four, Cambridge University Press, 2016, pp. 227–34.

Fang, Hui. “Cannibalizing Collective Memory: Chinese History and Political Consciousness in Tsui Hark’s The Taking of Tiger Mountain.” Continuum, vol. 34, no. 5, 2020, pp. 776–89. https://doi.org/10.1080/10304312.2020.1807464.

Ferrari, Rossella. Performance and Postsocialism in Postmillennial China. of Elements in Theatre, Performance and the Political. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2025.

Hung, Chang-tai. Mao’s New World: Political Culture in the Early People’s Republic. 1st ed., Cornell University Press, 2011. https://www.jstor.org/stable/10.7591/j.ctt7zj5t.

Jones, Andrew F. Circuit Listening: Chinese Popular Music in the Global 1960s. Minneapolis: University of Minnesota Press, 2020.

Kraus, Richard Curt. Pianos and Politics in China: Middle-Class Ambitions and the Struggle over Western Music. Oxford University Press, 1989.

Li, Jie, and Enhua Zhang, editors. Red Legacies in China: Cultural Afterlives of the Communist Revolution. Vol. 18 of Harvard Contemporary China Series, Harvard University Asia Center, 2016.

Mackerras, Colin. “The Taming of the Shrew: Chinese Theatre and Social Change since Mao.” The Australian Journal of Chinese Affairs, no. 1 (1979): 1–18. https://doi.org/10.2307/2159071.

Mittler, Barbara. A Continuous Revolution: Making Sense of Cultural Revolution Culture. Harvard East Asian Monographs, Harvard University Asia Center, 2012.

Murray, Noel. "The Taking Of Tiger Mountain." The Dissolve, 1 June 2015, https://thedissolve.com/reviews/1621-the-taking-of-tiger-mountain/.

Ouyang, Lei X. Music as Mao’s Weapon: Remembering the Cultural Revolution. University of Illinois Press, 2022. https://www.jstor.org/stable/10.5406/j.ctv2782dhb.

Rebull, Anne Elizabeth. “Theaters of Reform and Remediation: Xiqu (Chinese Opera) in the Mid-Twentieth Century.” Knowledge UChicago, University of Chicago, 2017. https://knowledge.uchicago.edu/record/863.

Taking Tiger Mountain by Strategy (智取威虎山). Directed by Xie Tieli, performances by Tong Xiangling and Shi Yuxiang, Beijing Film Studio, 1970.

The Taking of Tiger Mountain. Directed by Tsui Hark, performances by Zhang Hanyu, Lin Gengxin, and Tony Leung Ka-fai, Bona Film Group, 2014.

Zelizer, Barbie. "Cannibalizing memory in the global flow of news." In On media memory: Collective memory in a new media age, pp. 27-36. London: Palgrave Macmillan UK, 2011.